Dieser Bericht erschien in der Tacheles Ausgabe 17.

Im letzten Jahr haben sich erneut mehrere Arbeiter von Flink bei uns gemeldet – Anlass war mal wieder die Praxis von Flink, mit ihren Arbeiter*innen umzugehen, wie es ihnen gerade in den Kram passt. Dabei handelt Flink ohne jegliche Rücksichtnahme auf die Bedürfnisse oder Sicherheit der Arbeiter*innen, geschweige denn die Umsetzbarkeit der geforderten Arbeitsleistungen. Dabei setzt selbst einfachstes Arbeitsrecht ihrem Verhalten keine Grenzen (siehe dazu auch „Klage gegen Flink“ in Tacheles Ausgabe 15).

Wir wollen hier einen dieser Arbeiter von Flink zu Wort kommen lassen, dessen Erfahrung beispielhaft für ein System steht, in dem Flink und ähnliche Unternehmen bewusst Arbeiter*innen in prekären Lagen einstellen. Diese können sich nur schwer gegen das Vorgehen wehren, weil ihr Lebensunterhalt und häufig auch ihr Visum an den Arbeitsverhältnissen hängt. Der Verlust des Jobs kann hierbei im schlimmsten Fall zur Abschiebung führen.

Im letzten Jahr haben sich erneut mehrere Arbeiter von Flink bei uns gemeldet – Anlass war mal wieder die Praxis von Flink, mit ihren Arbeiter*innen umzugehen, wie es ihnen gerade in den Kram passt. Dabei handelt Flink ohne jegliche Rücksichtnahme auf die Bedürfnisse oder Sicherheit der Arbeiter*innen, geschweige denn die Umsetzbarkeit der geforderten Arbeitsleistungen. Dabei setzt selbst einfachstes Arbeitsrecht ihrem Verhalten keine Grenzen (siehe dazu auch „Klage gegen Flink“ in Tacheles Ausgabe 15).

Wir wollen hier einen dieser Arbeiter von Flink zu Wort kommen lassen, dessen Erfahrung beispielhaft für ein System steht, in dem Flink und ähnliche Unternehmen bewusst Arbeiter*innen in prekären Lagen einstellen. Diese können sich nur schwer gegen das Vorgehen wehren, weil ihr Lebensunterhalt und häufig auch ihr Visum an den Arbeitsverhältnissen hängt. Der Verlust des Jobs kann hierbei im schlimmsten Fall zur Abschiebung führen.

Es lässt sich häufig beobachten, dass Menschen dazu neigen, ihre eigene prekäre Situation zu rationalisieren und zu rechtfertigen. Wir können von Menschen nicht erwarten, radikale klassenkämpferische Thesen zu formulieren, die häufig eh nicht mit Inhalt gefüllt werden können. Stattdessen müssen wir gemeinsam einen Weg zu einer klassenkämpferischen Theorie und Praxis finden.

Es folgt ein Bericht eines Arbeiters bei Flink, in englischer Sprache:

When I first came to Germany, job opportunities were limited because I didn’t speak German. After seeing Flink riders working near our building, I applied and started working there. In the beginning, things were quite relaxed. Our hub manager was rarely present, and the workplace lacked structure. Because there weren’t many orders, the workload wasn’t intense either. Still, we had some recurring issues – for instance, the delivery boxes on the bikes would sometimes fall off, and for a long time, no one took responsibility for fixing them. Occasionally, other riders would attempt to make repairs themselves. About a year later, a new manager was appointed. Not long after his arrival, around ten riders were let go. Presumably, they were dismissed due to underperformance, as the work environment had not been properly managed until that point. After the new manager took over, the hub became more organized and the bikes were maintained more regularly. However, with so many people suddenly fired, many of us started worrying about our own job security. Some even began searching for other jobs, just in case. We weren’t really informed about any of these changes.

Soon after, the app began displaying our delivery times in real-time. Not only that – it also started warning us when we were “late.” Since this feature was new, the data wasn’t always accurate. Personally, I didn’t find this to be a helpful policy. It created unnecessary pressure. I noticed some riders – especially at night – began taking risks in traffic just to avoid being marked late. At the same time, our hub manager introduced a new “reward” system: the fastest rider of the month would receive two Too Good To Go bags. I’ll let you decide how motivating that really was.

To be fair, there were riders who didn’t follow the rules. Some would hang around the hub chatting instead of marking themselves as “available” in the app. If you didn’t do that, you wouldn’t receive any new deliveries. The new manager tried to crack down on this, but the fear of being fired became so widespread that I remember feeling anxious even about taking a short bathroom break. Technically, you’re allowed to use the restroom or drink water, but there’s no option in the app to mark a short break. There’s no clear limit, either. If you needed a 20-minute break due to an emergency, there’s a chance you could be penalized – but no one really knows.

During this time, more people were dismissed – sometimes without being given a clear reason. I’m not suggesting that everyone was following the rules, but management seemed to rely more on firing people than on communication or constructive supervision. Their approach felt unprofessional and distant. Most Flink riders are Master’s students. I wasn’t. I came to Germany with my wife, who works, so we were financially more stable. When I felt overwhelmed, I would open up my shifts for others to take. According to the system, you have to make yourself available for 150% of your contracted hours. You can release assigned shifts for others to take, but they’re not always picked up. My contract was for 20 hours, but I was usually given no more than 18. That didn’t bother me too much, but many of my colleagues were unhappy about it. As you can imagine, these students not only have to pass their exams but also learn German. While I could dedicate more time to language learning, many others struggled to find time beyond their studies and work. Only a few arrived already speaking German. Many of them had dreams of building a better life here, but found themselves doing physically demanding delivery work instead. Despite being engineers or other professionals in their home countries, they had to choose this job to survive. Over time, it led many to question whether they had made the right decision.

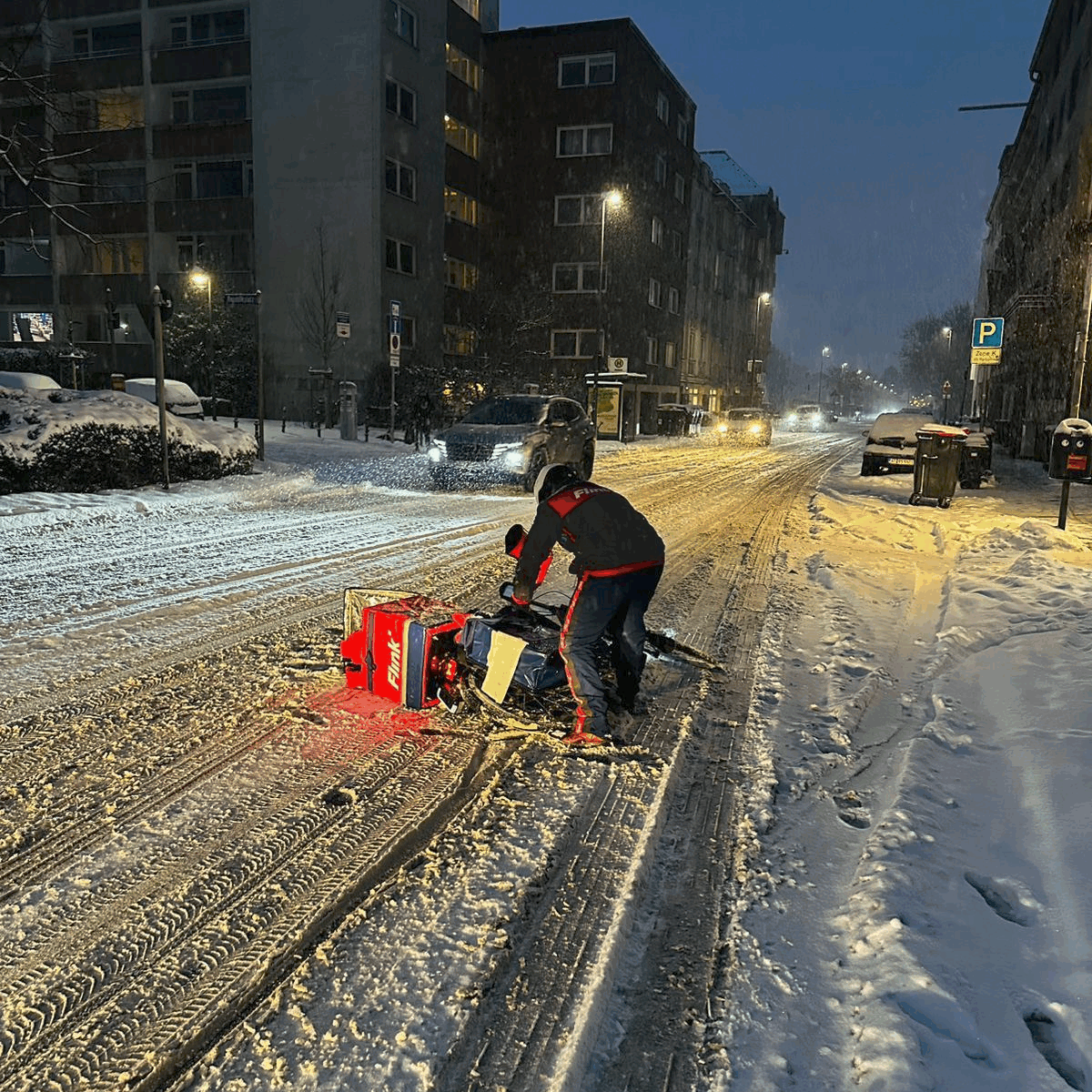

As things got busier, we were asked to carry four bags at a time. But our bikes weren’t designed for that. Many of us tried to squeeze the extra bag into the back somehow. Eventually, management introduced a front-mounted bag, but having a heavy load on the handlebars is risky and can affect balance and safety. I probably don’t need to explain what it’s like delivering orders with multiple bottles of beer or heavy drinks. It’s common, and it’s simply treated as a normal part of the job. I’m not even counting the huge 8-9 bag orders that came in occasionally. Later, they introduced bikes that could technically carry that amount – but these so-called e-bikes were actually weaker than standard ones. I still don’t know who makes these decisions or why we’re never consulted.

Last summer, I enrolled in a government funded B2 German course. I attended daily, so I worked fewer shifts and opened many of them up for others. If no one picked them up, I worked them myself. But I guess this didn’t sit well with our hub manager. One day, I received a new contract proposing fewer hours. I didn’t sign it. When asked why, I explained that my course was temporary and I’d soon be able to work more again. A month later, I started receiving shifts in Mönchengladbach – where I don’t live. I didn’t go, and eventually, I was dismissed.

I still don’t fully understand my manager’s overly aggressive approach. It seemed he was more focused on improving statistics in Aachen to boost his own career. He systematically got rid of anyone who didn’t fit into his vision and probably saw himself as completely justified. Before I left the team’s WhatsApp group, he had set his profile photo as the North Korean leader and claimed he was “better than him”. When someone scratched his car, he offered €100 to anyone who revealed the culprit.

To be honest, I’m not too sad for myself. I was planning to leave anyway. But I do feel sorry for the people still working there. Their families might proudly say their children are studying abroad, but they come home exhausted after hours of riding in the snow or rain and still have to prepare for exams. Winter shifts can literally freeze your body. In the rain, there’s no way to avoid getting soaked. And they can’t afford to complain – because if they can’t prove they’re earning enough money, their residence status and student visas are at risk. That’s why, at the very least, I’m glad I can share this story.